In the layered archives of Earth’s geological history, a new chapter is being written—one that future stratigraphers may recognize as the indelible signature of the Anthropocene. Among the most striking markers of this epoch are not volcanic ash or glacial deposits, but rather the synthetic remnants of human ingenuity and carelessness: microplastics and meteoritic debris. These unlikely bedfellows, one born of industrial excess and the other of cosmic violence, now mingle in sedimentary layers across the planet, forming a strange new kind of "jewelry" for the rock record.

The term "Anthropocene" itself remains unofficial, yet its proposed stratigraphic evidence is mounting. Microplastics—those fragmented, weathered shards of water bottles, fishing nets, and polyester clothing—have infiltrated even the most remote corners of the globe. Found in Arctic ice cores, abyssal ocean trenches, and the very air we breathe, these polymer particles exhibit a stubborn persistence. Unlike organic matter, which decomposes, or metals, which oxidize, plastics fracture into ever-smaller pieces without truly vanishing. Their chemical stability, once touted as a manufacturing virtue, now ensures their immortality in the geological ledger.

Meanwhile, extraterrestrial interlopers continue their ancient bombardment. Meteoritic dust, rich in nickel and iridium, has settled onto Earth’s surface for eons, leaving subtle but detectable traces in sediment layers. The Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, famously marked by an iridium spike from the dinosaur-killing asteroid, demonstrates how cosmic debris can punctuate geological time. Today, as microplastics rain down alongside these star-born particles, future geologists may puzzle over the juxtaposition of human-made and celestial materials fused in strata.

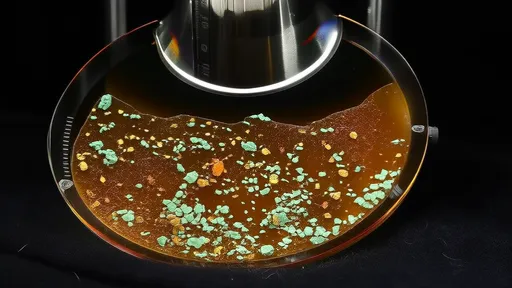

The deposition patterns of these materials reveal unsettling narratives. Ocean currents sort microplastics into swirling gyres, where they form ephemeral islands before sinking to the seafloor. Wind carries lighter particles to alpine lakes and polar regions, creating depositional layers as distinct as volcanic tephra. Meteoritic dust, by contrast, arrives more democratically—a fine mist of primordial matter across continents. Together, they create laminated "jewelry" in mudstones and sandstones: glittering microplastic fragments nestled against the dull sheen of space-derived metals.

Laboratory experiments with artificial sediments show how these materials might fossilize. Under pressure, some plastics undergo partial mineralization, bonding with silicates to form hybrid synthetic-natural composites. Meteoritic particles, already rich in rare minerals, resist alteration. The resulting strata could resemble banded agate—stripes of technofossils and cosmic dust visible to the naked eye. Such layers would differ radically from the organic-rich shales or limestone beds that dominate most of Earth’s history.

Beyond their geological novelty, these deposits raise profound questions about planetary health. Microplastics now cycle through ecosystems like nutrients, ingested by plankton and migrating up food chains. Some polymers adsorb toxicants, becoming poison pills for marine life. Meteoritic metals, though natural, arrive in ecosystems already stressed by pollution. The combined load—human-made and extraterrestrial—may leave ecosystems doubly burdened in the fossil record.

Curiously, both materials carry symbolic weight. Meteorites represent the uncontrollable forces that shaped Earth’s past; microplastics embody humanity’s unchecked dominion over its present. Their coexistence in strata mirrors our paradoxical relationship with nature—simultaneously vulnerable to cosmic randomness and arrogantly destructive. Future civilizations, if they unearth these layers, may read them as a cautionary tale of a species that reshaped the planet before understanding its place in the cosmos.

Efforts to mitigate microplastic pollution—biodegradable alternatives, filtration systems—lag far behind production rates. Meanwhile, meteorites continue their indifferent descent. The geological "jewelry" they form together will likely outlast not only our cities and monuments, but perhaps humanity itself. In this light, these strata become less a scientific curiosity and more a memento mori for an entire epoch.

Some researchers speculate about how to "curate" the Anthropocene’s legacy. Could future geoengineers mine sedimentary plastic for reprocessing? Might meteoritic metals become valuable markers for dating our era? Such questions feel both premature and quaint—assuming a future where humans retain control over Earth’s systems. The reality may be simpler: these layers will exist because we lacked the collective will to prevent them.

As drilling rigs extract ice cores and sediment samples, the Anthropocene’s proposed "golden spike" location remains debated. Whether in a Canadian lake’s plastic-laden mud or a coral reef’s synthetic fibers, the evidence mounts. What seems undeniable is that two seemingly unrelated materials—one forged in factories, the other in supernovae—now intertwine in Earth’s crust. They are the unintended collaborators in a stratigraphic revolution, the glittering, problematic jewelry of our age.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025