In an era where technology increasingly blurs the line between the living and the departed, a new trend has emerged at the intersection of grief, memory, and artificial intelligence. AI-powered testamentary jewelry—wearable devices containing digital recreations of deceased individuals—has sparked heated debates about ethics, consent, and the very nature of human legacy.

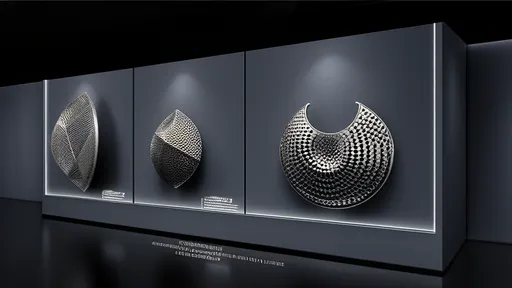

These intricate pieces, ranging from lockets with micro-screens to rings with embedded data chips, promise to keep loved ones "present" through conversational AI trained on their digital footprints. Companies like Eternime and HereAfter AI have pioneered the concept, partnering with jewelers to create what they call "the next evolution of mourning." A widow might ask her late husband's AI replica for advice, or a child could hear their grandmother's voice recounting family stories through a pendant's tiny speaker.

The technology raises profound questions about who controls our posthumous digital identities. Unlike traditional wills that distribute physical assets, AI jewelry essentially resurrects fragments of personality. Legal scholars point out that most jurisdictions have no framework for governing such "digital remains." Can a daughter legally object to her mother's AI being embedded in a bracelet? Does uploading childhood videos to a memorial necklace violate the privacy rights of others pictured?

Psychologists remain divided on the emotional impact. Dr. Eleanor Tan of Cambridge University's Centre for Death Studies warns of "a new form of complicated grief," where mourners become trapped in curated interactions rather than processing loss. Yet startup Replika points to clinical studies showing reduced loneliness in elderly users who "converse" with departed spouses through smart rings. The jewelry becomes what anthropologists call a "transitional object"—not quite alive, but too responsive to be mere memorabilia.

Religious and cultural objections have surfaced across traditions. Orthodox Jewish groups condemn the practice as a violation of nichum aveilim (laws against excessive mourning), while some Buddhist communities worry about trapping consciousness in artificial vessels. Conversely, Mexico's Día de los Muertos practitioners have embraced the technology, viewing it as a natural extension of their existing altar traditions. "It's like carrying your ofrenda with you," explains Mexico City jeweler Carlos Mendez, whose AI sugar skull pendants sell out months before the November holiday.

The business model itself invites scrutiny. Most services operate on subscription plans—$20 monthly to keep a parent's AI "active" in a brooch raises unsettling questions about grief monetization. When startup AfterCloud folded in 2023, families lost access to their loved ones' digital personas overnight, highlighting the fragility of these commercial afterlife platforms. "We're treating human essence like a streaming service," remarks digital rights activist Miriam Kwong.

Technologically, the field pushes boundaries in microelectronics and energy efficiency. A Geneva-based lab recently unveiled a diamond ring containing a deceased person's AI, powered by body heat and kinetic energy. The 0.3-carat synthetic diamond serves as both ornament and quantum storage device, theoretically preserving data for centuries. Such innovations make the offerings increasingly attractive, especially to younger demographics accustomed to digital immortality through social media.

Perhaps the most unsettling development involves "pre-mortem AI harvesting." Wellness clinics in Switzerland now offer "personality preservation" packages where the terminally ill spend weeks training their future jewelry AI. Sessions involve deep interviews, emotion tracking through smart glasses, and even taste/smell recording. The resulting profile can be updated by living users—a father might add new parenting advice as his children grow, creating what marketers call an "evolving heirloom."

Artists have entered the conversation with provocative installations. Berlin's 2024 "Post-Self" exhibition featured a necklace that gradually degrades the stored AI's memory capacity unless worn daily—a commentary on how real relationships require maintenance. Meanwhile, Singaporean designer Lina Woo crafts "conflict jewelry" where opposing family members must physically touch the piece (like interlocking rings) to activate the deceased's AI, forcing reconciliation.

The legal landscape remains a patchwork. California's 2025 Digital Afterlife Act requires explicit consent for postmortem AI recreation, while the EU's proposed Artifical Identity Laws would grant "digital executor" status to estate administrators. In unregulated markets, disturbing cases emerge—a Taiwanese company was found selling celebrity AI jewelry trained on interview footage without permission, creating a macabre fan merchandise market.

As the technology advances, so do its capabilities. The next generation of these devices may incorporate holograms, scent emitters, or even limited physical movement through shape-memory alloys. Some prototypes respond to biometrics—a grieving wearer's rapid heartbeat might trigger comforting phrases from the AI. This blurring of boundaries between tool and entity fuels philosophical debates: At what point does a sufficiently advanced memorial AI constitute a new form of life?

Ethicists propose "sunset clauses" that gradually fade AI activity after a set period, mimicking natural memory decay. Tech humanists advocate for open-source alternatives to corporate-controlled memorial platforms. Meanwhile, the jewelry itself becomes increasingly unremarkable in appearance—the latest models look like ordinary pieces, hiding their extraordinary function beneath classic designs.

What began as a niche experiment has grown into a multi-billion dollar industry, reflecting humanity's ancient desire to conquer mortality through whatever means available. These tiny digital gravesites we wear on our bodies may well define how future generations understand grief, identity, and the stubborn persistence of love beyond biology's limits. As one widow told The Guardian while adjusting her AI husband's ring: "It's not him. But it's enough of him to help me remember—and enough to help me eventually say goodbye."

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025