In a world dominated by visual stimuli, where aesthetics often dictate value and desirability, a groundbreaking exhibition is challenging the very foundations of how we perceive and appreciate art. "The Tactile Jewelry Exhibition for the Blind" is not just an art show—it's a sensory revolution that questions the hegemony of sight in our understanding of beauty.

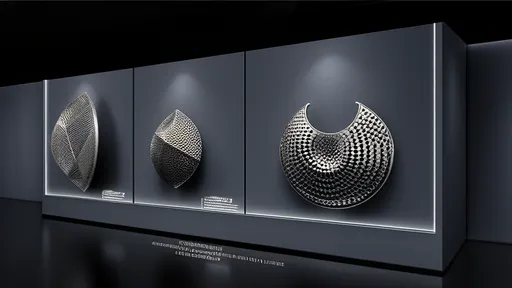

The exhibition, currently touring major cultural capitals, represents a radical departure from traditional jewelry displays. Instead of glass cases and "do not touch" signs, visitors are encouraged to close their eyes and explore intricate pieces through their fingertips. What emerges is an entirely new vocabulary of appreciation—one based on temperature, texture, weight, and the subtle vibrations of materials in motion.

Curator Elena Marcos, herself visually impaired since birth, explains the philosophy behind the project: "We live in a society that privileges vision above all other senses. This creates not just physical barriers for the blind, but conceptual ones for everyone. When we say something is 'beautiful,' we almost always mean 'beautiful to look at.' This exhibition asks: can a piece be beautiful to touch? To hear when its elements move? To feel against your skin?"

The jewelry pieces themselves defy conventional expectations. One standout work by Japanese artist Hiroshi Nakayama consists of nested silver spheres that emit different resonant tones when rolled in the palm. Another, by Brazilian designer Carla Mendes, incorporates rare woods and heated ceramic elements that change texture at body temperature. Perhaps most revolutionary is a collaborative piece that uses shape-memory alloys to "morph" under the touch, creating an interactive experience that evolves with each encounter.

Scientific research underpins many of the designs. Neuroscientists consulted for the exhibition emphasized how tactile perception activates different neural pathways than visual stimuli. "The brain processes touch through the somatosensory cortex," explains Dr. Rachel Leland from Cambridge University. "This area doesn't just register physical characteristics—it's deeply connected to emotional centers. There's a reason we speak of things being 'heartwarming' or 'gut-wrenching.' Tactile art can bypass intellectual appraisal and speak directly to our embodied experience."

The social implications of the exhibition are profound. By centering blind and low-vision individuals not just as audience members but as cultural arbiters, the show challenges deeply ingrained ableist assumptions about art consumption. Visitor testimonials reveal sighted participants experiencing something akin to sensory culture shock—followed by revelation. "I realized how much I rely on my eyes," remarked one attendee. "Touching these pieces, I felt colors as temperatures, patterns as rhythms. It was like learning a new language of beauty."

Critics have noted how the exhibition inverts traditional power dynamics in art spaces. Rather than accommodating blind visitors as an afterthought (through braille descriptions or limited touch opportunities), the tactile experience becomes primary. Sighted visitors must adapt, often relying on blind or visually impaired guides to fully appreciate the works. This simple reversal exposes how thoroughly museum and gallery conventions cater to the seeing majority.

The commercial art world is taking notice. Several pieces from the exhibition have been acquired by major collectors, signaling a shift in how value is assigned to sensory experiences. Auction houses are experimenting with blindfolded viewings, while luxury brands have begun commissioning tactile-focused designs. Perhaps most significantly, art schools are introducing courses on non-visual aesthetics—a development that could reshape creative education for generations.

Beyond the art world, the exhibition sparks broader philosophical questions about perception and knowledge. In an age of digital overload where images circulate at unprecedented speed, the deliberate, intimate pace of tactile engagement offers a counterpoint. As philosopher Jean-Luc Petit observes: "Western thought has long equated seeing with knowing—'I see' means 'I understand.' This exhibition reminds us that understanding can come through the body, through slowness, through qualities that can't be captured in an Instagram post."

Organizers plan to expand the exhibition globally, with versions tailored to different cultural understandings of touch and materiality. Future iterations may incorporate scent and sound more deliberately, pushing further into multi-sensory territory. What began as an accessibility initiative has blossomed into a full-fledged artistic movement—one that doesn't just include the blind community but learns from its distinct ways of engaging with the world.

As museums reopen post-pandemic with heightened awareness of physical interaction, the timing seems providential. The exhibition offers a model for art that doesn't just survive without touch but thrives because of it. In doing so, it holds up a mirror to our sensory biases while pointing toward more inclusive, embodied ways of experiencing beauty. The revolution, it seems, will not be televised—it will be felt.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025