In a dimly lit workshop behind razor-wire fences, hands that once committed crimes now delicately string pearls and polish gemstones. This is the reality of prison jewelry programs proliferating across correctional facilities worldwide, where inmates trade skilled labor for reduced sentences. The ethical implications of such initiatives have sparked heated debates among policymakers, human rights advocates, and victims' groups.

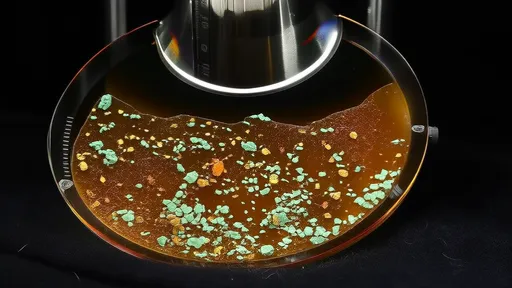

The concept seems straightforward at first glance: prisoners acquire marketable skills while producing luxury goods that fund rehabilitation programs. California's Prison Industry Authority reports their jewelry lines generate over $3 million annually, with similar programs operating in UK and Scandinavian prisons. Proponents argue these workshops provide purpose and professional training unavailable through traditional prison work like license plate manufacturing.

Yet beneath the polished surface lie troubling questions about exploitation and justice. Unlike standard prison jobs that pay cents per hour, jewelry-making inmates often receive no direct wages—their compensation comes solely through sentence reductions. This creates what Harvard criminologist Dr. Eleanor Voss calls "a moral accounting problem" where society struggles to quantify how many stolen years equal a handcrafted bracelet.

The programs disproportionately attract non-violent offenders serving mandatory minimum sentences, particularly women convicted of drug-related crimes. Former inmate turned jewelry designer Marisol Guevara recounts working 14-hour days to shave nine months off her sentence: "The guards called it rehabilitation, but we knew it was just another form of servitude with better PR." Her testimony echoes through prison reform circles, raising concerns about coerced labor dressed in vocational training clothing.

Victims' rights organizations present perhaps the most visceral objections. The National Association of Crime Victims recently protested when a Florida prison marketed inmate-made jewelry with the tagline "Redemption looks beautiful on you." Executive director Carla Mendes argues, "There's nothing beautiful about a burglar getting early release because he learned to set sapphires while his elderly victim still can't sleep at night." This emotional disconnect between product and producer haunts the initiative's public perception.

Psychological research adds complexity to the debate. A 2022 Oxford University study found jewelry program participants had 23% lower recidivism rates compared to matched controls. Neurological scans showed enhanced prefrontal cortex activity—the brain region governing impulse control—after six months of detailed craftsmanship. These findings suggest the programs may trigger genuine cognitive changes beyond simple behavior modification.

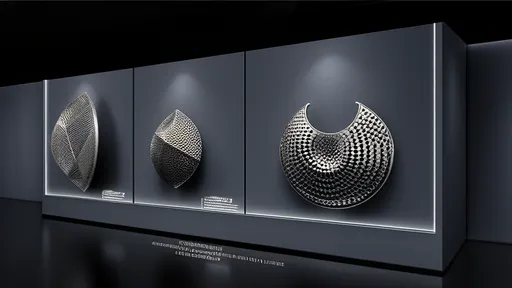

The luxury brands partnering with prisons face their own ethical reckoning. While Swiss watchmaker Chopard publicly severed ties with a Belgian prison program after media backlash, smaller designers like Second Chance Silversmiths proudly stamp their pieces with a tiny prison ID number. Consumer reactions split sharply along generational lines, with millennials showing three times more purchase intent than baby boomers according to market research firm Mintel.

International law adds another layer of scrutiny. The UN's Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners explicitly permits penal labor when "not subordinated to the purpose of making a profit." This creates legal gray areas when Tiffany & Co. subcontracts gemstone cutting to Indonesian prisons at 10% of free-world labor costs. Human Rights Watch has documented cases where refusal to participate in such programs results in loss of visitation rights or solitary confinement.

Perhaps the most profound dilemma emerges when the programs succeed. Master goldsmith Ricardo Torres, who served 12 years for armed robbery before his sentence was halced through jewelry work, now employs six former inmates at his Madrid workshop. "The system gave me back my life," he says, holding up a delicate filigree necklace, "but should it have? I don't know. That's for God and my victims to decide." His ambivalence encapsulates the moral vertigo surrounding these initiatives.

As correctional departments increasingly rely on inmate-made goods to offset budget cuts, the jewelry programs appear poised for expansion. New York's Sing Sing prison recently debuted a diamond-cutting program with an 18-month waiting list. Whether this represents progress toward restorative justice or merely a more palatable form of punishment remains society's unanswered question—one as multifaceted as the gems passing through prisoners' hands.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025