In the quiet laboratories of material scientists and the workshops of avant-garde jewelers, an unusual convergence is taking place. The marriage of nuclear science and wearable art has given birth to what might be humanity’s most paradoxical heirloom: jewelry embedded with actual nuclear waste. These pieces aren’t merely decorative; they’re designed to outlast civilizations, carrying warnings to future generations about the dangers buried beneath their feet.

The concept sounds like something torn from the pages of a dystopian novel, yet it’s rooted in a very real problem. For decades, governments and scientists have grappled with how to mark nuclear waste repositories in ways that remain intelligible for tens of thousands of years. How do you communicate danger to civilizations that might not share our languages, symbols, or even modes of perception? The answer, some suggest, might lie in objects so intrinsically valuable that they’d be preserved even as cultures rise and fall—objects like jewelry.

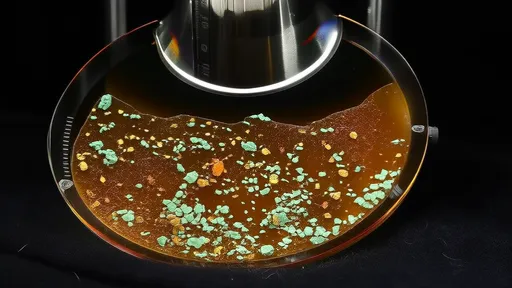

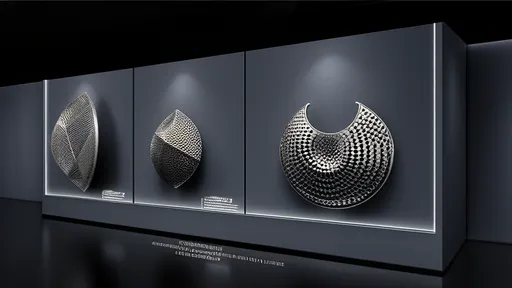

These radioactive adornments aren’t your typical pearls or diamonds. Crafted from materials like borosilicate glass infused with nuclear byproducts, the jewelry contains just enough radiation to be detectable with Geiger counters but not enough to pose immediate health risks. The pieces often incorporate intricate patterns or inscriptions in multiple languages, their designs intended to evoke both beauty and unease. One pendant might feature a swirling pattern reminiscent of radiation symbols, while a ring could bear microscopic text warning of buried waste nearby.

The idea taps into a deeper anthropological truth: humans have always used wearable objects to convey status, belief, and memory. From Egyptian amulets to Victorian mourning jewelry, adornments have served as cultural time capsules. Nuclear waste jewelry takes this tradition to its logical extreme, transforming personal ornamentation into a planetary early-warning system. The hope is that even if all other records of our civilization disappear, these artifacts would endure, their strange allure ensuring their preservation.

Critics argue that the project leans too heavily on speculative futurism. Could a piece of jewelry really survive millennia of geological shifts and societal collapses? And even if it does, would future civilizations interpret its message correctly, or might they mistake it for a sacred relic or a source of power? Proponents counter that the jewelry is just one layer of a larger strategy—a way to complement physical barriers and architectural warnings with something more personal and universally understood.

What’s perhaps most striking about these pieces is how they embody the contradictions of the Anthropocene. They’re at once beautiful and unsettling, a testament to human creativity and a reminder of our capacity for destruction. In wearing them, people become living monuments to a problem that will far outlast them, turning their bodies into vessels for a message they’ll never see delivered. It’s a poignant form of time travel, one that collapses the distance between present actions and future consequences.

The jewelry also raises provocative questions about value and legacy. In a world where we’re accustomed to thinking in terms of quarterly earnings or election cycles, these artifacts force us to confront scales of time that dwarf human comprehension. They ask us to consider what, if anything, we owe to generations so far removed from us they might as well be alien. And in doing so, they transform nuclear waste from an abstract policy issue into something tactile and intimate.

As climate change and other existential threats loom, the nuclear waste jewelry project hints at a broader shift in how we relate to the future. No longer content with passive hope, some are seeking active ways to embed warnings and wisdom into objects that might endure. Whether these efforts succeed remains to be seen, but their very existence speaks to a growing recognition: the choices we make today echo far beyond our own lifespans, and some messages are too important to leave to chance.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025