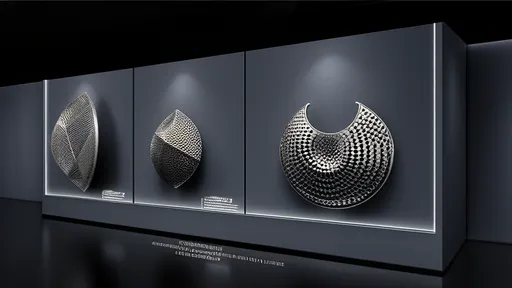

The human brain's reward system has long fascinated scientists and entrepreneurs alike. Recently, a new category of wearable devices has emerged that promises to hack this system - dopamine-stimulating rings that deliver mild electrical currents to the brain. These sleek, futuristic accessories claim to boost focus, enhance mood, and increase motivation by triggering the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter often called the "feel-good" chemical.

At first glance, these devices appear to offer a harmless way to optimize mental performance. Unlike pharmaceutical interventions, they're non-invasive and don't introduce foreign substances into the body. The technology builds upon decades of research into transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has shown promise in clinical settings for treating depression and other neurological conditions. However, the consumer-grade versions now hitting the market operate in a regulatory gray area, raising important questions about their long-term effects.

The science behind these rings is both compelling and concerning. By sending precise electrical impulses through the skin to targeted areas of the brain, they aim to stimulate the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens - key components of the brain's reward circuitry. Early adopters report immediate effects: heightened alertness, improved concentration, and a subtle euphoria similar to the afterglow of a good workout. But neuroscientists warn that regularly manipulating this delicate system could lead to unintended consequences.

One major concern is the potential for these devices to create dependency. The brain naturally maintains a careful balance of neurotransmitters, and artificial stimulation could disrupt this equilibrium. Chronic users might find their natural dopamine production diminishing as the brain adapts to the external stimulus - a phenomenon well-documented in substance abuse cases. Some researchers draw parallels to the tolerance buildup seen with stimulant medications, where users require increasingly larger doses to achieve the same effect.

The marketing of these products often downplays the risks while exaggerating benefits. Many companies position their devices as productivity tools rather than neurostimulators, using terms like "focus enhancement" instead of "brain stimulation." This framing makes the technology appear safer than it might actually be, particularly for vulnerable populations like students or overworked professionals seeking an edge. The lack of long-term studies means we don't yet understand the full spectrum of potential side effects, which could range from mild (headaches, irritability) to severe (mood disorders, cognitive dysfunction).

Another troubling aspect is the potential for misuse. Unlike clinical brain stimulation devices that require professional supervision, these consumer products come with no such safeguards. Users could theoretically wear them for extended periods or increase the intensity beyond recommended levels, chasing ever-stronger neurological effects. This self-administered, unmonitored use creates perfect conditions for developing compulsive behaviors around the device - a high-tech form of behavioral addiction.

The ethical implications become even more complex when considering how these devices might interact with existing mental health conditions. For individuals predisposed to addiction or mood disorders, artificial dopamine manipulation could potentially trigger or exacerbate problems. There's also the question of informed consent - can consumers truly understand the risks when the science itself remains incomplete? Regulatory bodies currently lack clear guidelines for these borderline products that straddle the line between wellness gadgets and medical devices.

Perhaps most concerning is how these devices might reshape our relationship with normal, everyday rewards. If people can get a dopamine hit at the push of a button, will they still derive satisfaction from natural pleasures like social connection, creative accomplishment, or physical exercise? Some experts worry we're entering an era where people might prefer the artificial certainty of neurostimulation to the messy unpredictability of real-world experiences that traditionally motivate human behavior.

The companies developing these technologies argue they're simply providing tools for self-optimization in an increasingly competitive world. They point to preliminary studies showing short-term benefits and emphasize the voluntary nature of use. However, critics counter that the very design of these products - with their instant gratification and sleek interfaces - follows the same psychological principles that make social media and video games so habit-forming. The difference is these devices work directly on the brain's reward circuitry rather than through behavioral cues.

As the technology advances, we may see more sophisticated versions capable of delivering increasingly precise neural stimulation. Future iterations might incorporate AI to customize stimulation patterns based on real-time brain activity or combine electrical stimulation with other modalities like light or sound. While such developments could unlock therapeutic potential, they also raise the stakes for potential misuse and addiction.

The emergence of dopamine-stimulating rings represents a watershed moment in consumer neurotechnology. These devices offer a tantalizing glimpse of a future where we can directly modulate our brain chemistry, but they also carry risks we're only beginning to understand. As with many emerging technologies, the line between empowerment and endangerment appears frustratingly thin. What begins as a tool for occasional productivity enhancement could, for some users, become a crutch they can't function without - the very definition of addiction.

In the absence of comprehensive research and clear regulations, consumers are left to navigate these waters largely on their own. The fundamental question remains: Just because we can hack our brain's reward system, should we? The answer may depend on whether we can develop these technologies with appropriate safeguards, or whether the allure of artificial dopamine proves too tempting to resist.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025