The legend of the crystal skulls has captivated imaginations for over a century, weaving together threads of ancient mysticism, archaeological intrigue, and modern commercialism. These enigmatic artifacts, purportedly crafted by the Maya or other Mesoamerican civilizations, are said to possess supernatural powers—from healing energies to apocalyptic prophecies. Yet behind the romanticized narratives lies a more prosaic truth: the vast majority of these "ancient relics" are industrially produced replicas, mass-manufactured to feed a global market hungry for the occult.

The Birth of a Myth

The story of the crystal skulls begins in the late 19th century, when European explorers and antiquities dealers began circulating tales of mysterious carved skulls discovered in Central American ruins. The most famous, the Mitchell-Hedges skull, was claimed to be a flawless quartz masterpiece of pre-Columbian origin—despite glaring inconsistencies in its provenance. By the mid-20th century, these objects had become fixtures of New Age lore, with proponents attributing to them everything from psychic communication to interdimensional portals. The 2008 film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull cemented their place in popular culture, transforming niche esoterica into mainstream fascination.

Factory-Made Mysticism

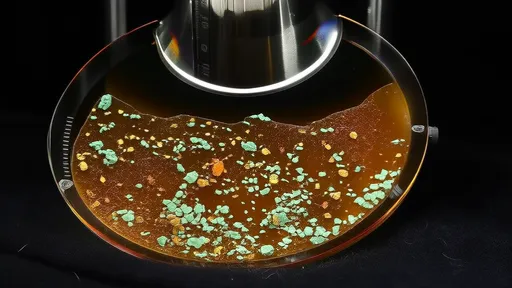

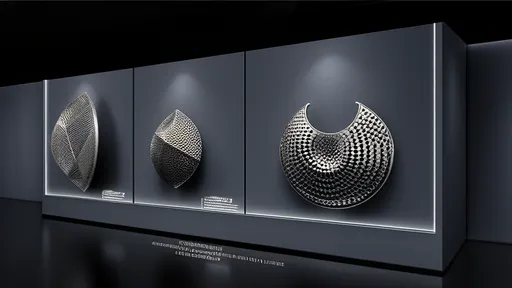

Modern forensic techniques have since exposed the uncomfortable reality: nearly all crystal skulls in museum collections and private hands are modern fabrications. Scanning electron microscopy reveals telltale machining marks from rotary tools impossible before the Industrial Revolution. Chemical analysis shows many were carved from Brazilian or Madagascan quartz—materials unavailable to ancient Mesoamericans. The British Museum and Smithsonian Institution have publicly acknowledged their skulls as 19th-century European creations, likely produced in German workshops specializing in exotic curios. Today, the city of Guangzhou serves as the epicenter of crystal skull production, where factories churn out thousands annually for the spiritual tourism trade.

The Spiritual-Industrial Complex

This industrialized mysticism thrives on deliberate ambiguity. Vendors in Mexican markets and online esoteric shops employ carefully crafted language—"in the style of ancient traditions" rather than outright claims of authenticity. Workshops in China's jewelry districts mass-produce skulls in every size and hue, from palm-sized amethyst carvings to life-sized obsidian specimens. The markup is staggering: a skull purchased wholesale for $20 may retail for $200 as a "sacred artifact," or $2,000 when accompanied by a certificate of energetic activation from a self-proclaimed shaman.

Why the Skulls Endure

Psychological and cultural factors explain the enduring appeal. The human brain is wired to seek meaning in patterns—a phenomenon called pareidolia, which makes us see faces (and by extension, skulls) in random shapes. Contemporary spiritual seekers, disillusioned with institutional religion but craving tangible connection to the divine, embrace these objects as physical anchors for their beliefs. The skull motif itself carries potent symbolism across cultures, representing both mortality and transcendence. In an age of digital alienation, the tactile nature of crystal—cool, heavy, refracting light—offers sensory satisfaction no app can replicate.

Archaeology vs. Pseudohistory

Legitimate scholars face an uphill battle against the skull mythology. Every scientific debunking seems to spawn new conspiracy theories about academic cover-ups. Contemporary Maya communities have expressed frustration at how their living culture gets reduced to marketable mysticism. "These fakes disrespect our ancestors," says Diego Mendez, a Yucatec Maya activist. "Real Maya art shows life—plants, animals, gods. Not just death symbols for foreign collectors." Meanwhile, looters continue destroying genuine archaeological sites searching for nonexistent crystal chambers, spurred by sensationalist television specials.

The Future of Manufactured Mysteries

As 3D printing and AI-generated provenance certificates make fakery increasingly sophisticated, the line between replica and "genuine fake" blurs further. Some contemporary artists now openly create crystal skulls as commentary on cultural appropriation—embedding RFID chips or corporate logos in the quartz. The phenomenon reflects broader tensions between spiritual longing and capitalist exploitation, between respect for ancient cultures and the human desire for wondrous objects. Perhaps the greatest mystery of the crystal skulls isn't their origin, but why we so desperately want them to be real.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025